Origins of the Order

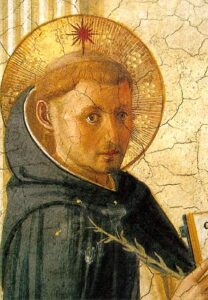

Dominique de Guzman

Dominique de Guzman is the founder of the Friars Preachers.

The evangelical man, as Jourdain de Saxe describes him in his Petit livre sur les origines de l’Ordre.

Who was this man?

Why did he found this community to which he himself gave the name of Friars Preachers, and which would later be commonly referred to by his name: the Dominicans?

St. Dominic has left us no written record to answer these questions.

So we have to question the chronicles that tell us about him, and what history tells us about his time, the Middle Ages.

Then we see the features of a man who aspired to just one thing: to imitate Jesus Christ.

A man, witnesses tell us, who spoke only with God or of God.

At the same time, Dominic reveals himself as a man in solidarity with a world in upheaval, a world he loves and wants to set ablaze with the fire of the Gospel that consumes him.

It was at the end of a long search for God’s plan, as he read it in the events that marked his life, that Dominic founded the Order of Preachers.

A world turned upside down

Saint Dominic was born around 1170 in the Spanish town of Caleruega.

Saint Dominic was born around 1170 in the Spanish town of Caleruega.

The medieval society in which he was to live and work for the Gospel was then in the throes of transition.

This was initially caused by one of the largest demographic explosions in history, accompanied by a vast urbanization movement.

Under the feudal system, activities such as trade and politics took place around the lords’ castles or abbeys.

Now, all this is shifting to the towns, which are becoming the poles of political and economic activity, whereas before they were merely places of settlement.

Alongside the nobility and clerics, this urbanization gave rise to a new social class: the bourgeoisie.

Important for the money they earned from trade, this merchant bourgeoisie ruled the city.

Local lords, sovereigns and churchmen now had to reckon with them, because it was they who could provide the money needed to maintain armies or finance construction.

But this population growth and urbanization did not bring prosperity to all; poverty was the common lot.

The majority of people had only the bare minimum to live on, their situation contrasting scandalously with that of the feudal nobility and the bourgeoisie.

In addition, epidemics and, above all, famines hit populations hard; free men revert to serfdom to ensure their subsistence.

At the same time, the English, French, Spanish and Germans are developing a national consciousness.

Their respective rulers are building their kingdoms on this nationalist basis.

The Church has not escaped this transformation.

Until then, its life had revolved around the abbeys.

These were almost the only places where people could receive advanced intellectual training, and where clerics could be recruited who were educated enough to become bishops.

Henceforth, schools moved from the abbeys to the cathedrals, i.e. to the city centers.

At first, cathedral schools provided only theological instruction for diocesan clerics.

But they soon expanded and opened up to a wider audience, offering instruction in all the sciences of the day (grammar, rhetoric, mathematics, philosophy) and giving rise to the universities.

In Saint Dominic’s time, the most famous were in Bologna and Paris.

Just as bourgeois merchants organized themselves into guilds under royal authority, so universities organized themselves into guilds under papal authority.

Despite this, the lower clergy – parish priests and chaplains – remain largely undereducated.

Generally speaking, these priests can neither read nor write, as they come from poor backgrounds and have not been able to study.

Having memorized the texts of a Mass and the corresponding Gospel, they repeat them tirelessly. When they preach, it’s not on the Gospel, but on a moral subject.

Paradoxically, Europe is Christian, but not evangelized.

The bishops are the ones who can correct this situation.

But more often than not, they are monopolized by the administration of the fiefs entrusted to them by the kings.

Originally, these estates had been given to them to provide income for the dioceses.

Over time, as these estates grew in size, bishops came to be regarded by the sovereigns as lords in the same way as a count or baron, and began to act as such.

The Church, in fact the Papacy, supported by a few bishops and sometimes a few sovereigns, tried to correct this situation.

Its main weapon was the creation of canons’ chapters in cathedrals.

These were priests living in poverty in community around the bishop.

These chapters are given the Rule of St. Augustine, which lays great stress on community life and poverty, and offers the example of the life of the early Church, as described in the Acts of the Apostles.

In the long term, it is hoped that these chapters will become nurseries for bishops who will conduct themselves more according to the Gospel ideal than that of the feudal nobility.

But this work of correction was slow in coming, and more and more voices were raised calling on the Church to abandon its riches and return to evangelical poverty.

These preachers found a sympathetic ear among the poor, who were joined by the lower clergy.

This was the origin of the great movements of return to the Gospel, whose motto was “to follow naked Christ naked”, which were to animate the whole of the 13th century.

Thousands of people attached themselves to these preachers and followed them on their travels.

In these movements, orthodoxy mingled with heresy.

The latter is often simply an over-reaction to a situation perceived as a betrayal of the Gospel.

In most cases, the preachers were lay people who had received rudimentary teaching of the Gospel.

These movements of poverty gave rise to mendicant orders such as the Premonstratensians, Franciscans and Dominicans.

From the schools of Palencia to the Chapter of Osma - Talking about God

It was during this period of upheaval and renewal that Dominique lived.

After receiving a basic education from one of his uncles, an archpriest, he was sent to the University of Palencia, Spain’s first, to learn the liberal arts.

Dominique soon opted to study theology.

During his studies, he made a name for himself by his diligence, spending entire nights deepening his knowledge of the Bible.

But this zeal for scrutinizing the Word of God did not cut him off from the world in which he lived.

During a famine that struck the whole of Spain, Dominic decided to sell his manuscripts and everything he had to help the poor.

He said, “I don’t want to study on dead skins when men are starving!” His gesture inspired many masters of theology to imitate him.

Dominic’s reputation soon reached his bishop, Diego d’Osma.

The chapter of canons in his cathedral had just been reformed according to the Rule of Saint Augustine.

Seeing the advantage of associating himself with such a man to consolidate the reform undertaken, he asked Dominic to become a canon.

Dominic accepted, attracted by the life of poverty and prayer.

The canons quickly realized the value of the newcomer and chose him as sub-prior, making him the bishop’s right-hand man.

His humility, gentleness and concern for others are remarkable.

He almost never leaves the cloister, the better to devote himself to prayer, meditation on scripture or texts by the Fathers of the Church.

But just when you might think that Dominic had cut himself off from the men and women of his time, he still carries them in his heart.

He no longer has anything to sell to help the unfortunate, but it’s to them that he thinks during the nights when intense prayer has replaced study.

During this prayer, he never ceases to ask God for effective charity to work for the salvation of the world.

Very often, these prayers are accompanied by tears and groans: “Lord, have mercy on your people! What will become of sinners?

Mission in Denmark - Talking about God

This solicitude for the salvation of the world soon found expression in fortuitous circumstances.

Diego d’Osma was asked by the King of Castile to negotiate the marriage of his son to a princess from Denmark.

The bishop sets off with his retinue, which includes Dominique.

They crossed the south of France, where the Cathar heresy was rampant.

Taking advantage of the movements for poverty and a return to the Gospel, the Cathars presented a dualistic doctrine in Christian guise, opposing a good God, creator of spiritual realities, and an evil God, creator of the material world.

In this context, detachment from worldly goods disguises contempt for all that is material.

Spending the night at an inn, Dominique learns that the owner is a Cathar.

He talks to the man for part of the night, and the man converts.

The bishop and his sub-prior continued on their way, arriving in Denmark.

Negotiations having been successfully concluded, they returned to Spain to report to the king, who sent them back to find the bride.

As the bride had died in the meantime, Diego passed on the news to the king and went to Rome with Dominic to meet the pope.

Preaching in Languedoc

In Denmark, the bishop had heard of the Cumans, a pagan people with barbaric customs.

So he asked the pope to relieve him of his diocesan duties so that he and his sub-prior could go and evangelize them.

The pope refused and sent them home.

On their way back to the south of France, Diego and Dominic meet the papal legates charged with preaching the Gospel and the faith against Cathar errors.

The legates complain to Diègue about the lack of success of their mission.

He soon realized that the Cathars’ success was due to the rigor and poverty of their preachers’ lives.

So he advised the legates to get rid of their escorts and horses and go and preach the Gospel on foot, taking only the necessary books with them.

Diègue immediately put his money where his mouth was, and set off to preach with Dominic, accompanied by the legates.

The year was 1206.

For two years, they preached like this: on foot and unescorted, throughout Languedoc.

Their preaching was quite successful.

A group of converted Cathar women, finding themselves without any means of support, were brought together by Dominic and his bishop to form a monastery in Prouille.

This monastery, the embryo of what was to become the Order of Dominican Nuns, served as Dominic’s headquarters after Diego’s death.

With Diego gone, the missionary legates dispersed.

The beginning of the Order of Preachers

From 1208 to 1213, Dominique carried on his preaching alone, while continuing to care for the monastery at Prouille.

He earned the respect of the Cathars through his rigorous lifestyle, good humor, poverty and zeal.

On the road, between villages, he walks barefoot.

He begs for bread and, when offered lodging, sleeps on the ground.

When he’s not preaching or exhorting conversion, he’s praying, and whenever he’s near a chapel or church, he goes there to celebrate the Eucharist or take part in liturgical prayer.

In time, a few men joined him to work on evangelization.

The small community first settled in a church in Fanjeaux.

Then, as two men from Toulouse gave themselves and their belongings to him, it moved to Toulouse.

Foulques, the city’s bishop, officially recognized the community and its preaching project in 1215, and granted it a portion of the poor’s tithe as income.

At the same time, Dominic entrusted the six brothers living with him to a master of theology for instruction.

Foulques de Toulouse travels to Rome to attend the IV Lateran Council, and Dominic accompanies him, seeking the pope’s approval for an order to be called the Order of Preachers.

The pope promised acceptance, on condition that Dominic and his brothers chose an existing rule.

On their return, they unanimously adopted the Rule of Saint Augustine.

Dominic returned to Rome to seek approval, which was then granted.

In 1217, Dominic dispersed his small community.

He sent his founders to Paris and Bologna, the university centers of the day, as well as to Spain and Rome.

From that point on, things moved quickly.

At first, Dominic’s friars aroused skepticism.

But soon enough, their poverty, devotion to prayer, preaching and evangelical life earned them an enthusiastic welcome wherever they went.

For example, the Paris convent, founded by two or three friars, numbered almost fifty when Dominic died four years later, not counting those who had left Paris to found elsewhere.

The first Chapter of the Order

As for Dominic, he went from convent to convent exhorting the brothers to stand firm.

He always went on foot to collect his bread.

In the convents he had neither cell nor bed, and despite the fatigue of the journey, he always spent his nights in prayer in the church.

In 1220, he convened the Order’s first General Chapter in Bologna, Italy, with each convent sending a number of brothers.

Once they had all gathered, Dominic asked them to choose another superior, as he considered himself unworthy of the office.

The brothers refused.

Then they adopted the first Constitutions of the Order, which regulated the life of the brothers by embodying in concrete provisions the Rule of Saint Augustine.

At this point, they took some important decisions: the Order had to give up its revenues, and each convent had to beg for its daily sustenance.

Finally, to better respond to the needs of evangelization, the Order was divided into provinces.

The death of Saint Dominic

With the chapter over, Dominic resumed his tour of the various convents. He was also entrusted by the Pope with a mission of evangelization in northern Italy. Then, in the summer of 1221, worn out by his endless walks and incessant vigils, he fell ill in Bologna. Realizing the seriousness of his condition, he asked for confession and communion. He then recommended himself to the brothers present, telling them that he would be more useful to them in heaven than on earth. He then passed away while the brothers commended his soul to God. Having died in someone else’s cell, since he had no cell in any convent, he was buried in the church, at the foot of the altar, wearing someone else’s tunic. His own, the brothers thought, was in too poor a condition: worn out, worn out… like the poor man it clothed.