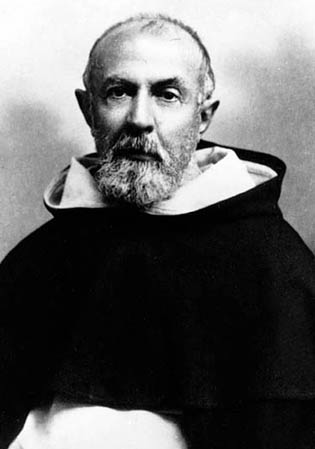

Marie Joseph Lagrange (1855-1938)

A controversial figure to whom scholars of the future will be forever indebted was Father Marie Joseph Lagrange, who founded the Biblical School of Jerusalem and who, almost alone, pioneered in Catholic scriptural studies in the light of modern archaeological research. Albert Lagrange was born near Autun in 1855, a frail child who gave every evidence of an early death. When he was three years old, his mother took him to Ars, where the saintly Cur& blessed him. Whether it was this blessing or the intercession of Our Lady of Autun that restored the little boy to health we do not know, but he recovered and set out early on the path of study.

The young Albert Lagrange had a varied career before becoming a Dominican. He studied law for five years and received his law degree, then spent a year in military service before entering the major seminary as Issy. While there, he decided to become a religious. He went to the Dominican convent of St. Maximin near Marseilles, and received the habit and the religious name Marie Joseph. The day after his profession in 1880, religious orders were once more expelled from France. Brother Joseph ryas sent to finish his studies at Salamanca, where he managed to get in extra work in Hebrew. By the time of his ordination in 1883, his superiors were well aware of his gifts, and he was sent to Vienna to study oriental languages.

In 1890 the young Father Lagrange arrived in Jerusalem and began his life’s work of founding a school of biblical research on the site of the martyrdom of St. Stephen, in an undistinguished old building which had belonged to the Dominicans for some time. His head full of plans, he looked soberly at the material he had to work with: a building which had once been the city slaughterhouse, and a library consisting of the two books he had brought with him a Bible and a guidebook of Palestine. Preliminary investigation disclosed that a great deal of archaeological work was going on in the neighborhood, and that Catholic scholars had not yet taken it into account. He set out from practically nothing to build up a school that would have no apologies to make.

A vast amount of exploring and scientific work had been done, mostly by critical and unbelieving scientists, who used their information to tear down traditional faith in the Bible and to attack Christian beliefs. Father Lagrange had only one objective, to make the Bible better understood. The means to be used were the modern ones of scientific research methods unknown to scholars of former times. In order to do his work, a thorough knowledge of the ancient peoples of the Bible was vital their history, customs, language, and religious beliefs. His law training was of great help in the study of the ancient law codes, and he rejoiced at the discovery of the code of Hammurabi and other material remains of ancient civilization.

He made long tiring trips by camel back to explore the sites of biblical events, and soon began raising a cloud of opposition by his critical analysis of both time and place in Scripture. He had the blessing of Pope Leo XIII, who as early as 1892 approved the research of the Biblical Institute. When they began, in the same year, to publish some of their conclusions, there was a murmuring of excited disagreement from traditional scholars, but the Holy Father approved wholeheartedly of the plan. The same pope who gave his enthusiastic backing to the new translation of St. Thomas and promulgated the study of the prince of theologians wished for an equally authoritative study of Scripture.

It is difficult for anyone not a Scripture student to follow the work of Father Lagrange. Scholars of all nations and of all faiths have come to value it, and we who are of his family should be proud that the man who opened the way for scientific scriptural studies was our brother. He had nothing but contempt for those timid scholars who were afraid to evaluate scientific discoveries for fear they would testify against revelation. His writings soon gained him the name of being a “dangerous radical,” a label that Dominicans have worn with distinction since the day when a young priest from Spain laid his idea of a preaching order in front of Pope Innocent III. The controversy which raged over the head of Father Lagrange saddened him at times, but never embittered him. At one time, several of his Old Testament studies were listed as “forbidden” to young students in seminaries, which was not a condemnation. Pope Pius X did not always share his predecessor’s trust of Father Lagrange, and the fact that he listened to the detractors of the great scholar was brought up adversely at the canonization process, indicating that Father Lagrange had been completely vindicated by time.

After forty five years in Jerusalem, Father Lagrange was forced by ill health to return to France. He had been a warrior for historical and scientific truth all of his long life, and it was not easy to settle down to a quiet life in the cloisters of St. Maximin. That he did it, and so humbly and unprotestingly, was a great edification to all. The pen that had swiftly and accurately produced an almost unbelievable array of scripture studies was still active for the remaining three years of his life. On the day before his death, he was sitting up in bed correcting proofs of his latest book, his keen mind undimmed and his fighting spirit unpacified. While one critic shouted that he was “too conservative” and another thundered that he was “too advanced,” he serenely finished his last article for the Revue Biblique, and said peacefully, “I abandon myself to God,” and murmured “Jerusalem, Jerusalem” as he passed into unconsciousness. He died on March 10, 1938.

Father Marie Joseph Lagrange was the recipient of many professional honors; he was made a member of the Legion of Honor and of the Order of Leopold, and the Dominican Order had very early named him master in sacred theology. It is the considered opinion of scholars that he had done for biblical criticism what St. Thomas did for Aristotle, and that his foundation of scientific research is the basis for all further study. Students trained in his spirit are dealing today with the “Dead Sea Scrolls” which were found a few years ago, and fearlessly making use of the truths that their study will reveal. Were it not for the courageous and brilliantly scientific methods of the Dominican founder of the Biblical Institute, Christian scholars might today be just beginning truly scientific studies of the Bible.

(Source : Dorcy, Marie Jean. St. Dominic’s Family. Tan Books and Publishers, 1983)